A brassiere (UK /ˈbræzɪər/ or US /brəˈzɪər/), commonly referred to as a bra /ˈbrɑː/, is a woman’s undergarment that supports her breasts. Bras are typically form-fitting and perform a variety of functions and have also evolved into a fashion item.

Women usually wear bras to support their breasts, which may be related to their desire to conform to social norms such as a dress code. Many women mistakenly believe bras prevent breasts from sagging. In fact, breasts naturally sag as a woman ages, depending on her breast size and other factors. Some researchers have found evidence that wearing a bra may actually contribute to sagging because they weaken the supporting ligaments.

Changing social trends and novel materials have increased the variety and complexity of available designs, and allowed manufacturers to make bras that in some instances are more fashionable than functional. Bras are a complex garment made of many parts, and manufacturers’ standards and sizes vary widely between brands, making it difficult for women to find a bra that fits them correctly. Even methods of bra-measurement vary, such that even professional fitters can disagree on the correct size for the same woman. About 90% of western women wear bras, but about 75–85% of women who wear bras are wearing the wrong size. Researchers have found a link between obesity and inaccurate bra measurement. A badly fitted bra can contribute to a variety of health problems, including back pain, breast pain, neck and shoulder pain, numbness and tingling in the arm, and headaches.

Some women have sought breast reduction surgery to lessen the pain and physicians have found that wearing a correctly fitted bra may alleviate the symptoms. Alternatively, other research has shown that going braless may also eliminate pain. Going braless can be acceptable in certain social circumstances depending on how obvious it is and on the woman’s self-confidence. About 10% of women do not wear a bra simply because it is more comfortable. Some garments, such as camisoles, tank tops and backless dresses, have built-in breast support, alleviating the need to wear a separate bra. It is increasingly common for celebrities to appear braless in public.

The bra has become a feminine icon or symbol with cultural significance beyond its primary function of supporting breasts. Some feminists consider the brassiere a symbol of the repression of women’s bodies. Culturally, when a young girl gets her first bra, it may be seen as a rite of passage and symbolic of her coming of age.

Purpose

Bras function by distributing the breasts’ weight evenly around a woman’s torso. The majority of Western women choose to wear bras to conform to what they feel are appropriate societal norms and to improve their physical appearance

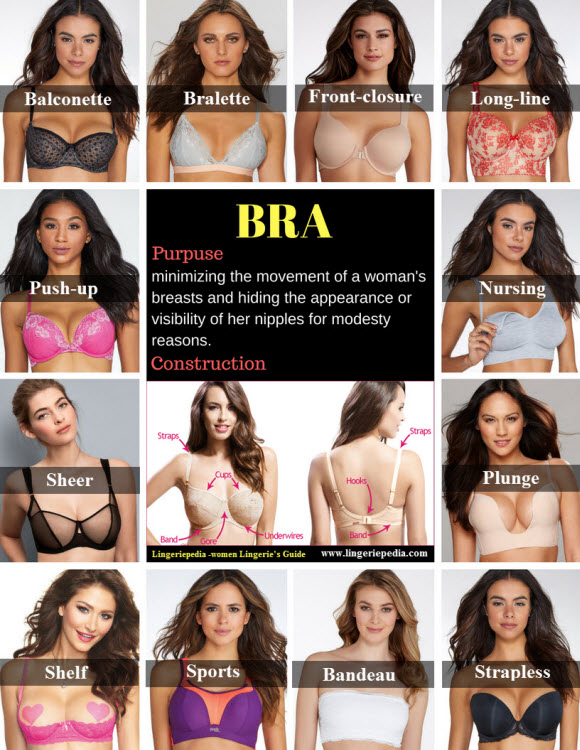

Social purposes include minimizing the movement of a woman’s breasts and hiding the appearance or visibility of her nipples for modesty reasons. Conversely, in other situations some women may choose to draw attention to their breasts by enhancing their perceived shape and size. Some women feel more comfortable wearing a bra, although a minority alternatively feel more comfortable without one.

Physical purposes include restricting breast movement during certain physical activities, supporting sagging breasts to give a more youthful appearance, supporting prosthetics after surgery, or to facilitate breastfeeding. Some specialized bras are designed for nursing or exercise.

Bras can also serve both purposes. Western culture places a great deal of importance on physical appearance, especially body shape, and wearing a bra can boost a woman’s self-confidence.

Etymology

The term “brassiere” was first used in the English language in 1893. It gained wider acceptance when the DeBevoise Company invoked the cachet of the French word “brassiere” in 1904 in its advertising to describe their latest bust supporter. That product and other early versions of the brassiere resembled a camisole stiffened with boning. Vogue magazine first used the term in 1907,and by 1911 the word had made its way into the Oxford English Dictionary. On 13 November 1914, the newly formed U.S. patent category for “brassieres” was inaugurated with the first patent issued to Mary Phelps Jacob. In the 1930s, “brassiere” was gradually shortened to “bra”.

In the French language, the term for brassière is soutien-gorge (literally “throat-support”). In French, gorge (throat) was a common euphemism for the breast. This dates back to the garment developed by Herminie Cadolle in 1905. The French word brassière refers to a child’s undershirt, underbodice or harness. The word brassière derives from bracière, an Old French word meaning “arm protector” and referring to military uniforms (bras in French means “arm”). This later became used for a military breast plate, and later for a type of woman’s corset.

In the French-speaking Canadian province of Quebec, both soutien-gorge and brassière are used interchangeably. The Portuguese word for bra is sutiã, while the Spanish use the word sujetador (from sujetar, to hold). The Germans, Swedes, Danes and Dutch all use the acronym “BH” which means, respectively, büstenhalter, bysthållare, brysteholdere and bustehouder (bust-holder). In Esperanto, the bra is called a mamzono (breast-belt). Despite the large number of nicknames for breasts themselves, there are only a couple of nicknames for bras, including “over-the-shoulder-boulder-holder” and “upper-decker flopper-stopper”.

History

Wearing a specialized garment designed to support a woman’s breasts may date back to ancient Greece. Women wore an apodesmos (Greek: ἀπόδεσμος), later stēthodesmē (Gr: στηθοδέσμη), mastodesmos (Gr: μαστόδεσμος) and mastodeton (Gr: μαστόδετον), all meaning “breast-band”, a band of wool or linen that was wrapped across the breasts that was tied or pinned at the back.

In 2008 archaeologists working at the Lengberg Castle in Eastern Tyrol, Austria, discovered 2700 fragments of textile, among them four bras. Two of them were modern looking bras, the other two were undershirts with incorporated cups. All bras were from linen. The two modern looking bras were somewhat similar to the modern longline brassiere with the cups made from two pieces of linen sewn with fabric extending down to the bottom of the torso with a row of six eyelets for fastening with a lace or string. The brassiere also has two shoulder straps and is decorated with lace between the cleavage, one of them possessing needle lace. The radiocarbon dating results showed that the four bras stemmed from the period between 1440 and 1485.

From the 16th century onwards, the undergarments of wealthier women in the Western world were dominated by the corset, which pushed the breasts upwards. In the later part of the 19th century, clothing designers began experimenting with various alternatives to the corset, trying things like splitting the corset into multiple parts: a girdle-like restraining device for the lower torso, and devices that suspended the breasts from the shoulder for the upper torso.

The first modern brassiere was patented by the German Christine Hardt in 1889. Sigmund Lindauer from Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt, Germany developed a brassiere for mass production in 1912 and patented it in 1913. It was mass-produced by Mechanischen Trikotweberei Ludwig Maier und Cie. in Böblingen, Germany. With metal shortages, World War I encouraged the end of the corset. By the time the war ended, most fashion-conscious women in Europe and North America were wearing brassieres. From there the brassiere was adopted by women in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

A design recognized as the modern bra was patented in 1914 in the United States by Mary Phelps Jacob.

Like other clothing, brassieres were initially sewn by small production companies and supplied to various retailers. The term “cup” was not used to describe bras until 1916, and manufacturers relied on stretchable cups to accommodate different sized breasts. Women with larger or pendulous breasts had the choice of long-line bras, built-up backs, wedge-shaped inserts between the cups, wider straps, power Lastex, firm bands under the cup, and even light boning.

In October 1932, the S.H. Camp and Company correlated the size and pendulousness of a woman’s breasts to letters of the alphabet, A through D. Camp’s advertising featured letter-labeled profiles of breasts in the February 1933 issue of Corset and Underwear Review. In 1937, Warner began to feature cup sizing in its products. Adjustable bands were introduced using multiple eye and hook positions in the 1930s.

Since then, bras have replaced corsets and bra manufacture and sale has become a multi-billion dollar industry. Over time, the emphasis on bras has largely shifted from functionality to fashion.

Although in popular culture the invention of the bra is frequently attributed to men, in fact women have played a large part in bra design and manufacture, accounting for half of the patents filed.There is an urban legend that the brassiere was invented by a man named Otto Titzling (“tit sling”) who lost a lawsuit with Phillip de Brassiere (“fill up the brassiere”). This originated with the 1971 book Bust-Up: The Uplifting Tale of Otto Titzling and the Development of the Bra and was propagated in a comedic song from the movie Beaches.

Construction and manufacturing

Mechanical design

Bra designers liken designing a bra to building a bridge, because similar forces are at work. Just as a bridge is affected vertically by gravity and horizontally by earth movement and wind, forces affecting a bra’s design include gravity and sometimes tangential forces created when a woman runs or turns her body. “In many respects, the challenge of enclosing and supporting a semi-solid mass of variable volume and shape, plus its adjacent mirror image—together they equal the female bosom—involves a design effort comparable to that of building a bridge or a cantilevered skyscraper.”

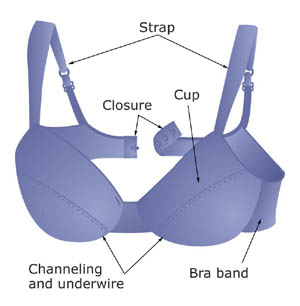

Bras are built on a square frame model. Their main components are a chest band that wraps around the woman’s torso, two cups to hold the breasts, and shoulder straps. The chest band is usually closed in the back by a hook and eye fastener, but may be fastened at the front. Some bras, particularly sleep bras or athletic bras, do not have fasteners and are pulled on over the head and breasts. The section between the cups at the front is called a “gore”. The section under the armpit where the band joins the cups is called the “back wing”.

Bra components, including the cup top and bottom (if seamed), the central, side and back panels, and the straps are cut based on manufacturer’s specifications. Many layers of fabrics are usually cut at once using a computer-controlled laser or a bandsaw shearing device. The pieces may be assembled by piece workers on site or at various locations using industrial grade sewing machines, or by automated machines. Coated metal hooks and eyes are sewn in by machine and heat processed or ironed into the two back ends of the bra band and a tag or label is attached. Some bras now avoid tags and print the label information onto the bra itself. The completed bras are transported to another location for packaging, where they are sorted by style and folded (either mechanically or manually), and packaged or readied for shipment.

The chest band and the bra cups are designed to support the weight of women’s breasts, not the shoulder straps. Some bras, called strapless bras, do not use shoulder straps but rely on underwire and additional seaming and stiffening panels to support the breasts. The shoulder straps of some sports bras cross over at the back, to take the pressure off an athlete’s shoulders when arms are raised. Manufacturers continually experiment with proprietary frame designs. For example, the Playtex “18 Hour Bra” model utilizes an M-Frame design.

Constructing a properly fitting brassiere is difficult. Adelle Kirk, formerly a manager at the global Kurt Salmon management consulting firm that specializes in the apparel and retail businesses, said that making bras is complex.

Bras are one of the most complex pieces of apparel. There are lots of different styles, and each style has a dozen different sizes, and within that there are a lot of colors. Furthermore, there is a lot of product engineering. You’ve got hooks, you’ve got straps, there are usually two parts to every cup, and each requires a heavy amount of sewing. It is very component intensive.

Materials

Before the advent of modern fabrics, fabrics like linen, cotton broadcloth, and twill weaves that could be sewn using flat-felled or bias-tape seams were used to make early brassieres. Bras are now made of a wide variety of materials, including Tricot, Spandex, Spanette, Latex, microfiber, satin, Jacquard, foam, mesh, and lace, which are blended to achieve specific purposes.

Spandex, a synthetic fiber with built-in “stretch memory”, can be blended with cotton, polyester, or nylon. Mesh is a high-tech synthetic composed of ultra-fine filaments that are tightly knit for smoothness.

From 60-70% of bras sold in the United Kingdom and the United States use underwire in the cup. The underwire is made of metal, plastic, or resin. Underwire is built into the bra around the perimeter of the cup where it attaches to the band, increasing the rigidity of the bra. The underwire improves support, lift and separation. Wirefree or softcup bras support breasts using additional seaming and internal reinforcement. Some types of bras like T-shirt bras utilize molded cups that eliminate bra seams and hide the woman’s nipples. Others use padding or shaping materials to enhance bust size or cleavage.

Manufacturing standards vary

To mass-produce bras, manufacturers size their bras to a prototypical women assuming she is standing with both arms at her sides. The design also assumes that both breasts are equally sized and positioned. Manufacturing a well-fitting bra is a challenge since the garment is supposed to be form-fitting but women’s breasts can vary in volume, width, height, composition, shape, and position on the chest. Manufacturers make standard bra sizes that provide a “close” fit, however even a woman with accurate measurements can have a difficult time finding a correctly fitted bra because of the variations in sizes between different manufacturers. Some manufacturers create “vanity sizes” and deliberately mis-state the size of their bras in an attempt to persuade women that they are slimmer and more buxom. Scientific studies show that the current system of bra sizing is quite inadequate.

Variance in bra sizes

There are several sizing systems in different countries. Most use the chest circumferences measurement system and cup sizes A-B-C+, but there are some significant differences. Most bras available usually come in 36 sizes, but bra labeling systems used around the world are at times misleading and confusing. Cup and band sizes not only vary around the world but between brands in the same country. For example, most women assume that a B cup on a 34 band is the same size as a B cup on a 36 band. In fact, bra cup size is relative to the band size, as the actual volume of a woman’s breast changes with the dimension of her chest. In countries that have adopted the European EN 13402 dress-size standard, the torso is measured in centimetres and rounded to the nearest multiple of 5 centimetres (2.0 in).

Types of bras

There is an increasingly wide range of brassiere styles available, designed to match different body types, situations, and outer wear. The degree of shaping and coverage of the breasts varies between styles, as do functionality, fashion, fit, fabric, and color. Common types include backless, balconette, convertible, shelf, full cup, demi-cup, minimizing, padded, plunge, posture, push-up, racerback, sheer, strapless, t-shirt, underwire, unlined, soft cup, and sports bra. Many designs combine one or more of these styles. Bras are built into some garments like camisoles, single-piece swimsuits, and tank tops, eliminating the need to wear a separate bra.

Alphabetical list of brassiere designs

- Adhesive: Sometimes described as backless/strapless bras or a stick-on bra. Usually made of silicone, polyurethane, or similar material, they are attached to the underside of the breasts using medical-grade adhesive. Some versions provide one piece for each breast. May be reused for a limited number of times and provides little support. Suitable for backless and strapless outerwear where a strapless bra is not possible or preferred, or as an alternative to going completely braless.

- Athletic: See Sports bra.

- Bandeau: A simple band of material, usually stretchy, that is worn across the breasts. Suitable for small-busts, they sometimes have built-in cups, but provide little support or shaping. A band of cloth can sometimes be used to bind the breasts in place.

- Balconette: Sometimes known as a shelf bra. Lifts the breasts to enhance their appearance, shape, and cleavage. More revealing version of a demi-bra, offering little to no coverage. The name means ‘little balcony’ which could refer to the shape; it is also claimed, less plausibly, that the name comes from the notion that the bra is not visible from above, as when looking down from a balcony. First designed in the United States in about 1938, and came into mainstream fashion in the 1950s. Compare to full-cup and demi-cup bra.

- Bralette: A lightweight, simple design, usually an unlined, soft-cup pullover style bra. The breasts are covered but the bra offers little, if any, real support and is suitable for small busts. Sometimes sold built-in to a camisole. This style is often used by preadolescent girls as a training bra.Similar to bandeau.

- Built-in: Sometimes described as a shelf bra, although completely unlike the shelf bra described below. Contained within or as an integral part of an outer garment like a swimsuit or tank top. Some built-in bras are detachable. They provide brassiere-like breast support utilizing a horizontal elastic strip like a bandeau, although some are shaped with cups and underwire.

- Bullet: A full-support bra with cups in the shape of a paraboloid with its axis perpendicular to the breast. The bullet bra usually features concentric circles or spirals of decorative stitching centred on the nipples. Invented in the late-1940s, they became popular in the 1950s due to ‘sweater girl’ pin ups. Madonna wore a bullet bra designed by Jean Paul Gaultier during her Blonde Ambition Tour which generated popular interest in vintage fashion. Vintage lingerie company What Katie Did was the first company to put the bullet bra back into production in 1999, and it has again grown in popularity with brands such as Marks and Spencer, Rigby and Peller and Naturana producing their own version of the bullet bra.

- Contour: Sometimes referred to as a molded-cup bra. Contour bras sometimes contain underwire. They have seamless, pre-formed cups containing a foam or other lining that helps define and hold the cup’s shape, even when not being worn. May be available as full-cup, demi-cup, push-up, or in other styles. Can be useful when breasts are asymmetrical (which is common – up to 25% of women’s breasts are asymmetric– or with enlarged or differently shaped nipples who want to create a symmetrical silhouette. ) Also see T-shirt bra, below.

- Convertible: The bra straps can be detached and rearranged in different ways depending on the outer garment. Alternative strap arrangements include traditional over-the-shoulder, criss-cross, halter, strapless and one-shoulder.

- Cupless: Like shelf bra.

- Demi-cup: Sometimes referred to as a half-bra or shelf bra. A partial-cup bra style that covers from half to three-quarters of the breast and creates cleavage and uplift. Most demi-cup bras are designed with a slight tilt that pushes the breasts towards the centre to display more cleavage. The straps usually attach at the outer edge of the cup. The lingerie industry generally defines a demi-cup bra as covering about 1 inch (25 mm) above the nipple.The underwire used is shorter and forms a shallower “U” shape under the cup. Suitable for low-cut outer garments. Compare to full-cup and balconnette bra.

- Front-closure: Bras with a single, non-adjustable clasp positioned in the centre front gore between the breasts.

- Full-support: Sometimes known as a full-figure or plus-size bra. A practical design that offers maximum coverage and support for larger busts.

- Full-cup: Designed to offer maximum support and coverage for the entire breast. A practical design for large-busted women. Compare to balconette and demi-cup bra.

- Jogging: See Sports bra.

- Leisure: Sometimes referred to as a sleep bra. These are very soft, stretchy, comfortable easy-to-wear bras that do not provide much support, suitable as everyday wear for small busts. They are an alternative to going braless and intended for wear at home when relaxing or asleep. With a large bust, bra support may increase comfort during sleep.

- Long-line: Extends from the bosom to the waist, offering additional abdominal control and smoothing of the woman’s torso. Distributes support over the entire lower torso instead of just the shoulders.

- Mastectomy: Designed to hold a breast prosthesis that simulates a real breast. Suitable after mastectomy.

- Male: Worn by men with enlarged breasts. Usually designed to flatten and conceal the breasts rather than to lift and support them.

- Maternity: A full-cup design with wider shoulder straps for maximum support and to reduce bounce. A practical design that uses comfortable fabrics to prevent irritation. May be adjustable to allow the cup size to expand as pregnancy develops.Sometimes known as a nursing bra, but does not utilize removable panels or cups that facilitate nursing an infant.

- Minimizer: Designed to de-emphasize the bosom, it compresses and reshapes the breasts. A practical design for large busts.

- Novelty: A fashion bra designed for appearance and sensuality. May include unusual materials, like leather or feathers. Includes unusual designs like the open-tip, peekaboo, or peephole bra that feature holes or slits in the fabric that reveal the areolas and nipples. Usually made of sensuous material like Lycra, nylon (nylon tricot), polyester, satin, lace or silk. Suitable for erotic situations.

- Nursing: Nursing Bra Like its sister the maternity bra, this is a practical bra designed with fuller cups, comfortable fabrics, and wider shoulder straps for increased comfort. Designed to support increased breast size during lactation. Aids breastfeeding by providing flaps or panels that can be unclipped and folded down or to the side, exposing the nipple. Underwire is not recommended for nursing bras because they can restrict the flow of milk and cause mastitis. Some designs utilize stretchable fabric allowing the bra to be pulled to one side to facilitate nursing.

- Padded: Designed to enhance perceived bust size and cleavage. The lining of the cups is thickened and enhanced with shape-enhancing inserts or foam padding inside the entire lining of cup. Padded bras support the breasts but, unlike push-up bras (see below), are not intended to significantly increase cleavage. Also see water bras below.

- Plunge: Sometimes known as U-plunge. Allows for lower and increased cleavage. Designed with angled cups and an open and lowered centre gore. The shoulder straps are usually set widely apart. Suitable for dresses or outfits with a deep décolleté or plunging neckline, like a blouse or dress. Unlike push-up bras, are not generally as heavily padded.

- Posture: Reinforce correct spinal posture and alignment.

- Push-up: A fashion bra that creates the appearance of increased cleavage. Use angled cups containing padding that pushes the breasts inwards and upwards, towards the centre of the chest. A push-up bra is usually a demi-cup bra. The Wonderbra was the first push-up bra made.

- Racerback: Designed with shoulder straps that form a “V” or “T” pattern between the shoulder blades. Suitable for outerwear like tank tops that would expose traditional over-the-shoulder straps. Provides extra support. Many sports bras use a racerback design to improve support and reduce bounce.

- Sheer: A fashion bra made of translucent material that displays the nipples.

- Shelf: Sometimes referred to as a cupless, open-cup, half-bra, or even quarter-cup bra. An underwire fashion design that offers minimal breast coverage, supporting only a portion of the underside of the breast, pushing the breast upward, and leaving the nipple and areola uncovered. Suitable for erotic purposes or when a woman would otherwise have to go braless.The exposed nipples may be visible beneath an outer garment. “Built-in bras” (see above) are sometimes referred to as a shelf bra.

- Soft cup: A practical design that does not use underwire for support. Traditionally regarded as offering less support than underwire models, soft-cup bras now offer competitive support and shaping. This is accomplished by using crisscross frames, inner under-cup slings that rise no more than half the height of the cup itself, and padding or lining the bra cup with 2-ply, molded, lined, or seamed material.

- Sports: Sports Bra Designed for athletic activities to provide firm support and minimize breast movement during exercise. Various designs are suitable for a range of exercise, ranging from yoga to running. Usually made of stretchable, adsorbent fabric like Lycra, and designed to wick perspiration from the skin to reduce irritation. (For bras worn by girls during puberty, see training bra.)

- Strapless: A fashion design that relies on an extra-wide band for breast support. Achieve their strength through a longer underwire that encompasses more of the breast, and cups with added padding, boning, and shaping panels. Suitable for bare-shoulder outer garments like a strapless evening gown that exposes the shoulders and chest, as low as the tops of the areola. Some convertible bras (see above) allow straps to be removed, making a strapless bra. It may have rubberized or silicone beading inside the top edge of the cup to help keep the bra attached to the breast. An alternative when an outfit would otherwise prevent a bra being worn.

- T-shirt: Designed without raised seams, hooks, or other construction that can be seen under an outer garment. A contoured style that fits the breasts smoothly under tightly fitting T-shirts, sweaters, light-weight knitted fabric, or clingy tops with minimal visibility. The cups may be lined with foam or lightly padded with polyfill to help conceal the nipples. Also see contour bra, above.

- Training: Designed to help conceal adolescent emerging breasts. As a girl’s breasts grow larger, usually around Tanner stage III, this style includes regular bras in smaller styles, from 30AAA to 32B. Most styles are a soft-cup, lightweight, unlined design. Some styles are padded. Also see bralette, above. For athletic-type bras, see sports bra.

- Underwire: Many bra designs feature a thin, semi-circular strip of rigid material that helps support the breast. The wire may be made of either metal, plastic or resin. It is sewn into the bra fabric and under each cup, from the center gore to under the wearer’s armpit.

- Water: Sometimes known as a liquid or gel bra. Contains water- or silicone gel-filled cups that enhance the size of the breasts. Air bras were a similar concept.

Correctly fitting bras

Because standards vary so widely, finding a correctly fitting bra can be very difficult for many women. Medical studies have also attested to the difficulty of getting a correct fit. Women tend to find a bra that appears to fit and stay with that size for a long period of time. As a result, 80–85% of women wear the wrong bra size.

Checking band fit

Symptoms of a badly fitted bra band include the band riding up the women’s back, indicating that the band is too loose. Experts recommend that the women reduce the band size. If the band digs into the flesh, causing the flesh to spill over the edges of the band, the band is too small. A woman can test whether a bra band is too tight or too loose by reversing the bra on her torso so that the cups are in the back and then check for fit and comfort.

Checking cup fit

If a woman’s breast tissue bulges out the side of the cup under the arm, under the cup, or over the cup, women should increase their cup size. If the cup fabric is loose, the cup is too large, and women should choose a smaller cup size. If the shoulder straps dig into the women’s skin, the woman should first attempt to adjust the shoulder straps. If that doesn’t reduce discomfort, then she should consider a larger cup size. If the straps slide off her shoulder, she should again first attempt to adjust the shoulder straps. If that doesn’t help, the woman should consider a smaller cup size. If the underwire doesn’t sit on the women’s chest or the gore doesn’t lie flat between the breasts, this indicates the women should buy a bra with a bigger cup size.

Bra experts recommend that women, especially those whose cup sizes are D or larger, get a professional bra fitting from the lingerie department of a clothing store or a specialty lingerie store.Generally, anytime a woman experiences a significant weight change, or if a woman has to continually adjust her bra or experiences general discomfort, the woman should get a new fitting.

Breasts inevitably sag

Many women mistakenly believe that wearing a bra prevents or slows their breasts from sagging and that breasts cannot anatomically support themselves. Researchers, bra manufacturers, and health professionals cannot find any evidence to support the idea. Fashion writers, bra makers, and medical authorities emphasize that wearing a bra is a matter of choice and not necessity.

Women’s breasts naturally sag as a woman grows older. In popular culture, this maturation is referred to as “sagging” or “drooping”, although plastic surgeons refer to it as ptosis. Robert Mansell, a professor of surgery at the University Hospital of Wales, in Cardiff, Wales, found in his research that “Bras don’t prevent breasts from sagging, with regard to stretching of the breast ligaments and drooping in later life, that occurs very regularly anyway, and that’s a function of the weight, often of heavy breasts, and these women are wearing bras and it doesn’t prevent it.”

Former Playtex Chief Executive Officer John Dixey told interviewers for the British documentary “Bras, Bare Facts” in 2000, “We have no evidence that wearing a bra could prevent sagging, because the breast itself is not muscle, so keeping it toned up is an impossibility…. There’s no permanent effect on the breast from wearing a particular bra. The bra will give you the shape the bra’s been designed to give while you’re wearing it. Of course, when you take it off, you go au natural.” Bras only affect the shape of breasts while they are being worn.

Factors affecting sagging

Contrary to popular belief, breastfeeding doesn’t contribute to sagging breasts.The biggest factors affecting whether and how much a woman’s breasts sag are the number of children she has had, her body mass index, the size of her breasts before pregnancy, and whether she smokes cigarettes. Cigarettes contribute to sagging because they break down elastin, decreasing the breast’s elastic appearance and external support. When breasts sag, the breast tissue folds down over the infra-mammary fold, the point where the underside of the breasts attach to the chest wall. As a result, the breast’s lower (inferior) surface lies against the chest wall. In some cases, the women’s nipple may even point towards the ground.

Heredity plays a part in breast size and shape, including helping determine characteristics like skin elasticity and the amount of breast tissue. Breast skin retains a youthful appearance through the contribution of a protein called elastin. Internally, the breasts are composed of the mammary glands which remain relatively constant throughout life, fat tissue which surround the mammary glands, milk ducts, and Cooper’s ligaments. The milk ducts don’t influence breast size until a woman becomes pregnant, and again when she begins lactating. It is the amount and distribution of adipose tissue and, to a lesser extent, glandular tissue, that leads to variations in breast size. The exact function of Cooper’s ligaments and their role in supporting breast tissue is not certain.

Bras may increase sagging

In France, three multi-year studies found that women’s breasts did not sag more after not wearing a bra, and that a woman’s breasts may actually sag more due to wearing a bra. Dr. Laetitia Pierrot and Dr. Jean-Denis Rouillon, sports physician at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, France have conducted several studies to determine if bras offer support as advertised and whether they prevent women’s breasts from sagging.

In 2003, Dr. Pierrot published the results of a year-long research project. She closely studied 33 women who were active in sports at least four hours per week. The women agreed to stop wearing a brassiere during both sports activity and at all other times for one year. Their position of their breasts and nipples were biometrically assessed four times during the year. Before the study began, a majority of the women reported some discomfort while wearing a bra. Pierrot found at the end of the year that 88% of the women reported feeling increased comfort. Her physical assessment of participants showed strengthened rotator and pectoral muscles, fewer stretch marks, and an overall improvement in the height of the women’s nipple-areola complex when measured relative to her shoulder. Contrary to popular belief, the women’s breasts did not sag further, but their position on the woman’s chest actually improved.

These findings were confirmed by Dr. Rouillon. In 2007, he published a 3-year-long study of 250 French women. During the study they measured the relative position of the women’s nipples relative to her shoulder blade, while both standing and lying down. The women’s breasts were measured every six months during the three-year period. Their breasts showed a statistically significant reduction in the distance from the nipple to the shoulder bones. It also noted that height of the nipples relative to the bottom of the breast improved. Rouillon concluded that women may choose to wear brassieres for social considerations but they do not permanently enhance a woman’s bustline.

In 2013, Rouillon updated his findings after 15 years studying the anatomy of 130 women under the age of 35. He concluded that bras are a “false necessity” and that they women would be better off not wearing a bra at all. He concluded that “Medically, physiologically, anatomically – breasts gain no benefit from being denied gravity.” The study found that the breasts of women who went without a bra for more than a year were firmer and sagged less.

One example is given of a woman who had breasts that were uncomfortably large, and who experienced improvement after two years of not wearing a bra. Dr. Rouillon theorizes that when women wear bras, the supporting ligaments become underused and weakened, causing breast tissue to sag further when women remove their bras.

In a much smaller Japanese study, 11 women aged 22-39 years were measured wearing a “well-fitted” brassière for three months and then went without a bra for another three months. The study found that after wearing the specially fitted bra for three months the women’s breasts were larger and hung lower. The underbust measurement decreased and the overbust measurement increased, while the lowest point of the breast moved downwards and outwards. The effect was more pronounced in larger-breasted women. This may be related to the particular bra chosen for the experiment, as there was some improvement after changing to a different model.

Health issues

A badly fitted bra can also contribute to health problems.The British Chiropractic Association warned that wearing the wrong bra size can lead to a number of problems, including restricted breathing, abrasions, breast pain, poor posture. The British Osteopathic Association reported that 60% of British women have experienced pain at some point from wearing a bra, including back pain, neck stiffness, and headaches, Some women sacrifice their health to wear fashionable bras.

Large breasts and bra fitting

When purchasing bras, larger-breasted women usually have difficulty selecting a well-fitting bra. Buxom women are more likely than smaller-breasted women to wear an incorrectly sized bra. They tend to buy bras that are too small, while smaller-breasted women tend to purchase bras that are too large.[1] When women wear a bra with too big a band size, the band will ride up on their back which may place pressure on their vertebrae at the top of the back and the bottom of the neck (vertebrae C6 and C7), causing back pain.

Because it’s harder for overweight women or women with larger, heavier breasts to find a well-fitting bra, the bra strap may ride up at the woman’s back and put strain on the trapezius muscle, causing back pain. Large-breasted women who wear a bra with size D or larger cups are particularly likely to experience health problems.

Buxom women have unique challenges in finding a correctly fitted bra. This may be due to inaccuracies inherent in the cup size measurement system, which was originally conceived for only four cup sizes: A through D. Other issues that affect a buxom woman’s ability to find the right bra include a lack of understanding of how to correctly determine bra size, difficulty in finding larger cup sizes, or unusual or unexpectedly rapid growth in size brought on by pregnancy, weight gain, or medical conditions including virginal breast hypertrophy.

In a study conducted in the United Kingdom of 103 women seeking mammoplasty, researchers found a strong link between obesity and inaccurate bra measurement. They found that all of the women in the study wore the wrong bra size. On average, women in the study were wearing too large a cup size (by a mean of three sizes) and too small a band size (by a mean of four inches). The researchers concluded that “obesity, breast hypertrophy, fashion and bra-fitting practices combine to make those women who most need supportive bras the least likely to get accurately fitted bras.”

Large-breasted women who wear an improperly fitted bra may experience maceration (loss of skin), chafing, intertrigo (rash), and fungal infections.

Asymmetrical breasts

In addition to the difficulties already described, up to 25% of women’s breasts are persistently and visibly asymmetrical, which plastic surgeons define as differing in size by at least one cup size. Ten percent of women’s breasts are severely different, with the left breast being larger in 62% of cases. Manufacturer’s standard brassiere sizes can’t accommodate these inconsistencies which makes it more difficult for women to find a well-fitting bra.

Bras and pain

Women wearing poorly fitting bras may experience breast pain, neck and shoulder pain, numbness and tingling in the arm, and headaches. Among a group of 31 British women who requested reduction mamoplasty, 81% complained of neck and back pain, while 77% complained of shoulder pain.

One long-term clinical study in 1987 showed that women with large breasts can suffer shoulder pain from wearing bras. In the study, E. L. Ryan of the University of Melbourne and colleagues found that the inherent design of bras causes fatigue and possibly shoulder pain. They showed that when women perform an activity that requires them to raise their arms above shoulder level, the weight of the woman’s breasts are transferred from the band around her torso to the bra straps. Bra straps put downward pressure on the scapula, effectively turning the shoulder into a pulley, doubling the total downward pull on both shoulders. The tension may be continuously present in large or heavy-breasted women. Researchers in Turkey found that women with who wore bras with cup sizes D and above experienced upper back pain due to changes in the curvature of the spine.

In Japan, about 13% of women report experiencing some form of shoulder pain, while in a 2006 survey of 339 female hospital employees, 59% of the respondents said their bra causes them to occasionally experience back, shoulder, or neck pain. The majority cited their bra straps as the biggest problem.

A woman who wears a bra with bra straps that are too tight puts extra pressure on the trapezius muscles that can lead to chronic pain. Tight bra straps transfer the weight of the breasts to the scapula and puts direct pressure on the serratus anterior and trapezius muscles which serve to elevate the scapula. The muscles become fatigued which may lead to back, shoulder and neck pain.Even strapless bras can cause problems for larger-breasted women. They put all the breasts’ weight onto the chest band and cause extra strain onto the rib cage and back.

Bras and physical activity

Up to 56% of women report some kind of breast pain when taking part in strenuous physical activity or exercise. A well-fitted bra, especially a sports bra, can help alleviate symptoms. Physicians recommend women who are experiencing breast pain may be able to reduce symptoms by wearing a better-fitting bra. A 1976 study of 114 women in the United Kingdom complaining of breast pain were professionally fitted with a special, custom-fitted bra. Twenty-six percent of women who completed the study and wore the bra properly experienced pain relief, 49% improved somewhat, 21% received no relief, and 4% experienced more pain. There were a lot of dropouts from the study.

Some occupations require women to repeatedly raise their arms above the shoulders. Female volleyball, high jump, or long jump athletes must continually lift their arms above their shoulders. This can cause the shoulder straps to dig in, putting the athletes at risk for shoulder pain. Even smaller-busted women who repeatedly lift their arms while wearing a poorly designed or badly fitted bras can experience shoulder pain.

To compensate, female athletes can wear athletic or sports bras, which are more effective than ordinary bras at reducing breast pain caused by exercise. However, sports bras may not meet some larger-busted women’s needs. Judy Mahle Lutter, president of the Melpomene Institute, a Minnesota-based research organization devoted to women’s health and physical activity, reports that “Larger-breasted women, and women who are breast-feeding, often have trouble finding a sports bra that fits, feels comfortable and provides sufficient motion control.”

Bra-free relief from pain

However, the need for wearing a bra at all during exercise has been questioned after extensive studies of athletes. In a French study, women who went braless were no more likely than women who wore bras to experience back pain. Some women even reported that the lack of a bra helped to reduce back pain. British research has indicated that post-menopausal women who wear a bra are more likely to suffer breast pain.

There are two studies that show going without a bra can reduce shoulder pain and one that wearing a bra can actually increase the amount that breasts sag. A Japanese study in 2012 of 339 women found that overweight women tended to have larger breasts, but that brassiere cup size was more indicative of the weight of the breasts than their breast size. They correlated cup size over breast size to shoulder-neck pain, which occurred in 13% of study participants.

This is consistent with other literature that suggests that it is wearing bras, and not a woman’s breast size, that causes larger-breasted women to experience breast pain. Two studies have found that going braless can help resolve shoulder and neck pain and may be a preferred treatment over reduction mammaplasty.

According to a study published in the Clinical Study of Pain, large-breasted women can reduce back pain by going braless. Of the women participating in the study, 79% decided to stop wearing bras completely.

In a five-year study, 100 women who experienced shoulder pain were given the option to alleviate the weight on their shoulders by not wearing a bra for two weeks. In that two-week period, a majority experienced relief from pain. Relief was complete among 84% of women who did not elevate their arms. However, their pain symptoms returned within an hour of resuming bra use. Three years later, 79% of the patients had stopped wearing a bra “to remove breast weight from the shoulder permanently because it rendered them symptom free.” Sixteen percent worked in occupations requiring them to elevate their arms daily, and this group only achieved partial improvement. Of these, 13 of the 16 ceased to wear a bra, and by six months all were without pain.

Fibrocystic disease and breast pain

Numerous websites and publications dealing with fibrocystic disease and breast pain state that a well-fitting bra is recommended for treatment of these conditions. A 2006 clinical practice guideline stated, “The use of a well-fitting bra that provides good support should be considered for the relief of cyclical and noncyclical mastalgia.” The study rated the statement as being supported by level II-3 evidence and as a grade B recommendation. However, this rests solely on two short, uncontrolled studies.

n a 2000 study in Saudi Arabia, 200 women were randomly allocated to receive either Danazole, a synthetic steroid ethisterone whose off-label uses include management of fibrocystic breast disease and breast pain, or a sports bra. Fifty-eight percent of the Danazole group improved compared to 85% in the sports bra group. No details of what the women wore before the study was given. Neither study used an untreated control or implemented double-blind controls. Breast pain has a very high placebo response (85%) so a response to any intervention can be expected. It is not clear whether the interventions described can be generalized to a large population.

Culture and fashion

Modern bras were invented at the beginning of the 19th century but are not universally worn around the world. Women choose to wear a particular style of bra for a variety of reasons. Many believe the bras prevent sagging, but this is not supported by any evidence.

Breast shape

Women’s bra choices are consciously and unconsciously affected by social perceptions of the ideal female figure reflecting her bust, waist, and hip measurement. The culturally desirable figure for woman in Western culture has changed over time. Fashion historian Jill Fields wrote that the bra “plays a critical part in the history of the twentieth-century American women’s clothing, since the shaping of women’s breasts is an important component of the changing contours of the fashion silhouette.” Bras and breast presentation follow the cycle of fashion.

Bra fashion

In the United States during the 1920s, the fashion for breasts was to flatten them as typified by the Flapper era. During the 1940s and 1950s, the sweater girl became fashionable, supported by a bullet bra (known also as a torpedo or cone bra) like those worn by Jane Russell and Patti Page.

After the feminist protest during the Miss America pageant on 7 September 1968, bra manufacturers were concerned that women would stop wearing bras. In response to the feminist era, many bra manufacturers’ marketing claimed that wearing their bra was like “not wearing a bra”.During the 1960s, bra designers and manufacturers introduced padded bras and underwire bras. Women’s perception of undergarments changed, and in the 1970s, they began to seek more comfortable and natural looking bras.

Each fall, Victoria’s Secret commissions the creation of a Fantasy Bra containing gems and precious metals. In 2003, it hired the jeweller Mouawad to design a bra containing more than 2,500 carats of diamonds and sapphires, taking over 370 man-hours to complete. German supermodel Heidi Klum later posed in the bra, which at the time was the world’s most valuable, at USD$10 million. In 2010, Victoria’s Secret hired designer Damiani to create a US$2 million Fantasy Bra. It includes more than 3,000 brilliant cut white diamonds, totaling 60 carats, and 82 carats of sapphires and topazes.

Visible bra and straps

During the 1990s, women in Europe, America and in some parts of Asia began to show their bra-straps, often as a fashion statement. Until that time, it was usually considered a faux pas for women to show their bra or bra straps in public. In some social circles, that is still true, putting women at risk as being seen as sloppy, slutty, trashy or immodest. Madonna was famously one of the first entertainers to break convention when she wore a cone brassiere as outerwear during her 1990 Blond Ambition tour. (Her brassiere from the tour sold for USD$52,000 at the Christie’s Pop Culture auction in London on November 29, 2012.)

It is increasingly common to see women wearing clothing that purposefully exposes a portion of her bra or bra straps in certain social situations. For example, Lindsay Lohan was seen showing her bra strips at Charlotte Ronson’s fashion show in 2009. In June 2009, singer Rihanna wore an orange, lace bra that was visible under a button-down top. In the televison series Sex and the City, Carrie Bradshaw, the character played by Sarah Jessica Parker, wore a top that revealed a lace bra. Demi Lovato appeared on Cosmopolitan’s August 2013 cover in a plunging orange dress that reveals the underwire-buttressed center of an ornate teal bra. The Fall 2013 Couture collection introduced by Versace prominently featured fashions that were open in the front, revealing underwire bras. Singer Selena Gomez was seen in public wearing bib overalls that exposed the sides of her torso and a black lace bra.

At the Paris premiere of L’Ecume Des Jours, Audrey Tautou wore a lace Dolce & Gabbana top that showed off her black bra. In London, actress Lucy Mecklenburgh, star of The Only Way Is Essex, wore a sheer lace top that clearly showed her black bra underneath.

While most companies and especially law firms have rather conservative dress codes, actress Julia Roberts as the title character frequently wore tops that revealed her Ultimo push-up bra and cleavage in the film Erin Brockovich. While at a New York City park on May 6, 2013, Jessica Alba wore a loose-fitting tank top that revealed she was wearing a sheer, black bra, and Sports Illustrated swimsuit model Kate Upton purposefully wore a sheer mini-dress that exposed her bra on a date on July 29, 2013. David Hacker, vice president of trend and color at Kohl’s, believes showing bra straps is acceptable.

Other women have exposed their bras in public to draw attention and raise funds for charities like breast cancer research. Wearing clothing that reveals the wearer’s bra or bra straps has become so common that Cosmopolitan and Seventeen created guidelines for women describing how to expose their bra straps or bras in an acceptable manner. The guidelines include avoiding flesh-toned, smooth-cup bras, so that the exposure looks deliberate and not accidental. They also recommend making sure the women’s bra is in good condition and to wear a style that provides ample coverage. Other advice includes wearing a flesh-colored bra or a bra that matches the color of the bra to the color of the sheer garment worn over them and don’t wear a bra that shows through the garment’s armholes.

Groundbreaking Wonderbra campaign

In May 9, 1994, a significant shift in advertising lingerie occurred. Advertising executive Trevor Beattie, working for TBWA/London, developed an ad for Sara Lee’s “Hello Boys” Wonderbra campaign. It featured a close-up image of Czech model Eva Herzigová in a black Wonderbra with ample cleavage and the title, “Hello boys.” The bra was introduced in New York City and Eva’s figure wearing the Wonderbra was featured on the large 2,800 square foot billboard in New York’s Times Square.Critics complained that the photograph demeaned women. The ground-breaking, racy ad campaign was repeated across the United States, resulting in an explosion of sales that Sara Lee could not meet. The Wonderbra began selling at the rate of one every 15 seconds, generating first year sales of about US$120 million. Many competitors introduced their own cleavage-enhancing bras.

John Dixey, former CEO of Playtex, said “the Wonderbra has made it into the Collin’s Dictionary. It has become an icon which is just as powerful as Levi’s jeans.” By the end of 1994, the Wonderbra had been named one of Fortune’s products of the year and was recognized by several other magazines including Advertising Age and U.S. News and World Report.

The billboard was voted in 2011 as the most iconic outdoor ad during the past five decades by the Outdoor Media Centre. The influential poster was featured in an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and it was voted in at number 10 in a “Poster of the Century” contest.

The Canada-based lingerie fashion label wanted the ad campaign to motivate women to see the Wonderbra “as a cosmetic and as a beauty enhancer rather than a functional garment”.Unlike prior bras whose purpose was to hide and de-emphasize woman’s “unmentionables”, the Wonderbra created and enlarged women’s cleavage. It marked the shift of the bra from a purely functional garment to a fashion item used “as a means of attraction.”

During 2002, Wonderbra began sponsoring National Cleavage Day in South Africa. The event is observed in early April each year. Push-up bras got significant attention in 2000 when actress Julia Roberts in the film Erin Brockovich enhanced her bust with an Ultimo push-up bra containing liquid silicone gel.

Miss America protest

During the Miss America contest on 7 September 1968, about 400 women were drawn together from across the United States by a small group, the New York Radical Women, in a protest outside the event. They symbolically threw a number of feminine products into a large trash can. These included mops, pots and pans, Cosmopolitan and Playboy magazines, false eyelashes, high-heeled shoes, curlers, hairspray, makeup, girdles, corsets, and bras, items the protestors called “instruments of female torture.” Carol Hanisch, one of the protest organizers, said “We had intended to burn it, but the police department, since we were on the boardwalk, wouldn’t let us do the burning.” A New York Post story by Lindsy Van Gelder about the protest drew an analogy between the feminist protest and Vietnam War protesters who burned their draft cards. In fact, there was no bra burning, nor did anyone take off their bra.

Hanisch said, “Up until this time, we hadn’t done a lot of actions yet. We were a very small movement. It was kind of a gutsy thing to do. Miss America was this ‘American pie’ icon. Who would dare criticize this?” Along with tossing the items into the trash can, they marched with signs, passed out pamphlets, and crowned a live sheep, comparing the beauty pageant to livestock competitions at county fairs.”The media picked up on the bra part,” Hanisch said later. “I often say that if they had called us ‘girdle burners,’ every woman in America would have run to join us.”

Feminist opinions

Some feminist writers have considered the bra an example of how women’s clothing has shaped and even deformed women’s bodies to historically aesthetic ideals, or shaped them to conform to male expectations. Professor Lisa Jardine observed feminist Germaine Greer talking about bras at a formal college dinner:

At the graduates’ table, Germaine was explaining that there could be no liberation for women, no matter how highly educated, as long as we were required to cram our breasts into bras constructed like mini-Vesuviuses, two stitched white cantilevered cones which bore no resemblance to the female anatomy. The willingly suffered discomfort of the Sixties bra, she opined vigorously, was a hideous symbol of female oppression.

Germaine Greer’s book The Female Eunuch has been associated with the ‘bra burning movement’ because she pointed out how restrictive and uncomfortable a bra in that time period could be. “Bras are a ludicrous invention,” she wrote, “but if you make bralessness a rule, you’re just subjecting yourself to yet another repression.” For some, the bra remains a symbol of restrictions imposed by society on women: “…the classic burning of the bras…represented liberation from the oppression of the male patriarchy, right down to unbinding yourself from the constrictions of your smooth silhouette.” While women didn’t literally burn their bras, some women stopped wearing bras as a form of rebellion or protest. By refusing to follow generally accepted norms, they intended to communicate their rejection of how society stratifies men’s and women’s roles.

Professor and feminist Iris Marion Young wrote that in U.S. culture breasts are subject to “Capitalist, patriarchal American media-dominated culture [that] objectives breasts before such a distancing glance that freezes and masters.” Some feminists suggest that when a young girl begins wearing a bra, it symbolically changes her breasts into sexual objects.

Bras and youth

When the Flapper era ended, the media substituted teen for Flapper. Olga manufactured a teen bra that was skimpy and sheer. Other manufacturers responded in kind. Since the end of World War II, a great deal of attention has been given to a girl receiving her first bra. It may be seen as a long-awaited rite of passage in her life signifying her coming of age.

Firm, upright breasts are typical of youth. As such, they may not physically require the support of a bra. A Pencil test, developed by Ann Landers, has sometimes been promoted as a criterion to determine whether a girl should begin wearing a bra: a pencil is placed under the breast, and if it stays in place by itself, then wearing a bra is recommended; if it falls to the ground, it is not.

Girls may choose to begin wearing a training bra designed for pubescent or teen girls who have begun to develop breasts during early puberty. They are available in sizes 30AA to 38B. Training bras are usually designed with a soft, elastic bra band and wireless bra cups. Prior to the marketing of training bras, a pre-teen or young teen girl in Western countries usually wore a one-piece “waist” or camisole without cups or darts. Bras for pre-teen and girls entering puberty were first marketed during the 1950s.

As a result of a long-term study over 15 years of 330 women aged 18 to 35, Dr. Jean-Denis Rouillon recommended that young girls delay or avoid wearing a brassiere. This will allow a girl’s ligaments and skin to strengthen and help support her breasts. Professor Göran Samsioe of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Lund University, Sweden’s oldest and largest university, suggested that girls with growing breasts who wear bras can negatively affect the development of elastic tissue beneath the skin that help support breasts. He said these tissues are developed by the “everyday, natural, movements” of the unsupported breasts. “If natural movement is restricted by a bra that is too tight, it can affect the growth of these tissues.” He cautioned that girls with unusually large breasts should wear a bra if needed, “as long as it allows your breasts to move in a natural way.” He cautioned girls against buying “highly supportive” or constrictive bras, expressing concern that they “are falling prey to societal pressures driven by the commercial interests of clothing manufacturers.” He said that girls are made to believe that they need to wear a bra, “but there is no medical reason for them and in some cases it can even be harmful.”

In the early 1960s, 96.3% of female college freshmen bought bras as part of their back to school wardrobe. At the tail end of the 1960s when bralessness increased as a trend, the number had slipped to 85%. Only 77% of high school girls bought bras as they prepared to return to school.

Social issues and trends

Consumers spend around $16 billion a year worldwide on bras. In 2012, women in the United States owned an average of 9 bras and wore six of them on a regular basis. That is an increase from 2006, when the average American woman owned six bras, one of which was a strapless bra, and one in a color other than white. The average bust size among North American women has increased from 34B in 1983 to a 34DD in 2013. The growth in bra size is due in part to the availability of a larger selection of bras to choose from and to women wearing better fitting bras.

Percentage wearing bras

Various surveys have reported that from 75% to 95% of Western women wear bras. According to underwire manufacturer S & S Industries of New York, who supply bras to Victoria’s Secret, Bali, Warner’s, Playtex, Vanity Fair and other bra labels, about 70 percent of bra-wearing women wear underwire bras.

In a cross-cultural study of bra size and cancer in 9,000 women during the 1960s, a Harvard group found 93% wore bras (from 88% in the UK to 99% in Greece), but could not find enough women in Japan who wore bras to complete their study. A Harris Survey commissioned by Playboy asked more than 1,000 women what they like in a bra. Among the respondents, 67% said they like wearing a bra over going braless, while 85% wanted to wear a “shape-enhancing bra that feels like nothing at all.” They were split over underwire bras, 49% said they prefer underwire bras while 49% said they prefer wireless bras.

Social norms

Women sometimes wear bras because they mistakenly believe they prevent sagging breasts. Others simply feel that bras improve their appearance. Some wear bras because they believe others might consider their behavior—the unrestrained movement of their breasts or the readily discerned appearance of their nipples under their clothing—as “lewd”. If a woman’s nipples or aerola can be seen through clothing, others may perceive this as “indecent” or inappropriate. Some women wear bras because they want to conceal the natural shape of their breasts and nipples, responding to cultural standards of modesty, or because they fear criticism or unwanted attention. Women’s nipples may become erect when stimulated by environmental factors like cold, so women wear bras because they fear that their erect nipples will draw undue or unwanted attention.

Bralessness

In prior generations, whether a women wore a corset reflected on her morality and her social standing. Only women of ill-repute or low social standing allowed themselves to be seen not wearing a corset. Wearing a corset became a way for a woman to communicate that she was a worthy female member of polite society. In the modern world, bralessness is not acceptable in some social or business circumstances, and some people may judge a woman’s social status depending on whether she is wearing a bra or not.

When a woman chooses to go braless, others may assume she’s making a political statement or that she wants sexual attention. On the contrary, women who go braless may simply desire to feel more comfortable. Some women, especially those with smaller busts, prefer to go braless and can get away with it more easily than larger-busted women. Women may wear bras because their work dress code requires it, but actually prefer going braless. Some women feel uncomfortable wearing a bra and take off their bras when they return home.

To avoid unwanted attention, women who want to go braless can choose clothing like camisoles that conceal their breasts and nipples or adhesive silicone nipple covers. Depending on the social context, women may wear different kinds of clothing to hide or reveal the fact that they’re not wearing a bra. Some outer garments like sundresses, tank tops, and formal evening wear are designed to be worn without bras or are designed with built-in support. In some social circumstances a woman may choose to go braless even when it is obvious to the casual observer.Unhappy bra owners have donated thousands of bras to the Braball Sculpture, a collection of 18,085 bras. The organizer, Emily Duffy, wears a 42B and switched to stretch undershirts with built-in bras because standard bras cut into her midsection.

Braless celebrities

Unlike employees of many companies, celebrities are not subject to dress codes with the exception of rare instances like the 55th Grammy Awards, which a number of celebrities ignored anyway.

Actress Marlo Thomas gave up wearing a bra on her television show That Girl in 1968, shortly after the feminist protest during the Miss America pageant. “God created women to bounce,” Thomas said. “So be it.” It is increasingly commonplace to see public figures, especially celebrities, actresses and members of the fashion industry, who have chosen not to wear a bra, at least on some occasions. British gardening expert and TV personality Charlie Dimmock hosted her gardening show Ground Force from 1997 through 2005 on BBC. Dimmock, who is large-busted, became well known for going braless at all times in all weather. Celebrity chef, television personality, and businesswoman Clarissa Dickson Wright only wears a bra on special occasions. In 2010, former model and France’s first lady Carla Bruni welcomed Russian president Dmitry Medvedev at a state dinner in a tight dress that revealed she was braless.More recently, singer Miley Cyrus has been noted for appearing in public on repeated occasions without a bra, and even announced via Twitter that she does not wear a bra.

Other celebrities noted for going braless on more than one occasion in public include Britney Spears, Claire Danes, Lindsay Lohan,Nadine Coyle, Mischa Barton, Meg Ryan, Paris Hilton, Lady Gaga, actress Tara Reid, and fashion executive Tamara Mellon.

Opposition to bras

Some people question the medical or social necessity of bras. Some researchers have found health benefits for going braless. (See health issues above.) An informal movement advocates breast freedom, top freedom, bra freedom, or simply going braless.

Bra opponents believe training bras are used to indoctrinate girls into thinking about their breasts as sexual objects. In their view, bras for very young girls whose breasts do not yet need support are not functional undergarments and are only intended to accentuate the girl’s sexuality. Feminist author Iris Young wrote that the bra “serves as a barrier to touch” and that a braless woman is “deobjectified”, eliminating the “hard, pointy look that phallic culture posits as the norm.” Without a bra, women’s breasts are not consistently shaped objects but change as the woman moves, reflecting the natural body. Unbound breasts mock the ideal of the perfect breast. “Most scandalous of all, without a bra, the nipples show. Nipples are indecent. Cleavage is good—the more, the better…” Susan Brownmiller in her book Femininity took the position that women without bras shock and anger men because men “implicitly think that they own breasts and that only they should remove bras.”

In October 2009, Somalia’s hard-line Islamic group Al-Shabaab forced women in public to shake their breasts at gunpoint to see if they wore bras, which they called “un-Islamic”. They told women that wearing a bra was deceptive and against Islamic teaching. Girls and women found wearing a bra were publicly whipped because bras are seen as “deceptive” and to violate their interpretation of Sharia law. A resident of Mogadishu whose daughters were whipped said, “The Islamists say a woman’s chest should be firm naturally, or flat.”

Individuals opposed to bras in the United States organized a “National No-Bra Day”, first observed on 9 July in 2011. The group encouraged women to go without a bra for the entire day. Women posted on Twitter comments about the relief they feel when taking off their bra. The lingerie firm Victoria’s Secret commented that the day was not good for their business. More than 250,000 people expressed support for the special day on a Facebook page dedicated to the event.

Legal issues

Transportation security

The United States Transportation Security Administration recommends that women do not wear underwire bras because they can set off the metal detectors.In response, Triumph International, a Swiss company, launched what it called a “Frequent Flyer Bra” in late 2001. The bra uses metal-free clasps and underwires made of resin instead of metal that are guaranteed to not set off metal detectors.

Prison security

In June 2010, attorney Brittney Horstman was prevented from meeting a client at the Federal Detention Center, Miami when her underwire bra set off a metal detector. She removed the bra in a bathroom and was then barred from entering the prison because she was now braless, a violation of the detention center’s dress code. The federal public defender’s office contacted Warden Linda McGrew, who conducted an inquiry. Prison guards had received a memo allowing women wearing underwire bras to enter the prison, but the guards on duty during Horstman’s visit were unaware of the modified policy.The warden concluded the incident was “an aberration” and promised it would not happen again.

In schools

In November 2009, parents and school officials complained about girls wearing sports bras and boys running shirtless before and after the Hillsborough County (Tampa area of Florida) Cross Country Championship track event. County athletic director Lanness Robinson informed the athletic directors of all of the Hillsborough County’s public schools of a school board policy that even though sports bras are designed as outer garments, they must be covered with at minimum a singlet (sleeveless T-shirt) and boys cannot go topless, no matter how hot it is. The policy applies to all events and training sessions.

Plant High (Tampa) girls cross country coach Roy Harrison reported that out of concern for his student’s safety, he would not follow the mandate. “We train all through August and September, when the heat index is 103 °F (39 °C), 105 °F (41 °C), 107 °F (42 °C) outside even in the evening and to me, it’s a safety issue not letting boys run without their shirts and girls in sports bras.” Coaches and athletes pointed out that sports bras, form-fitting compression shorts and running shirtless are common, as is wearing swimsuits and tight-fitting volleyball uniforms.

During 2012, Memphis, Tennessee Democrat Joe Towns attempted but failed to pass legislation that required female student athletes to wear shirts over their sports bras. Knosville Republican Bill Dunn was shocked at the way the girls athletes dress.

…having several children who play sports, it’s pretty shocking to me that you go to practices and games and young ladies are walking around in sports bras…would that be considered underwear?

Lawsuits

Victoria’s Secret was sued several times during 2009. The suits alleged that defective underwear contained formaldehyde that caused severe rashes on women who wore them. Six cases were filed in Ohio and two in Florida. At least 17 other suits were filed in six other states after January 2008. The plaintiff refused to submit to a simple patch test to determine the precise cause of her reaction and her case was later withdrawn. The Formaldehyde Council issued a statement that formaldehyde quickly dissipates in air, water and sunlight.

In employment

In January 2011, a German court ruled that employers can require female employees to wear bras or undershirts at work. An airport security firm argued that requiring bras was essential “to preserve the orderly appearance of employer-provided uniforms.” The court also agreed that the company could require employees to keep their hair clean and male employees to be clean shaven or maintain a well-trimmed beard.

In August 2011, Wendy Anderson of Utah sued her employer for sexual harassment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In her suit, she claimed that Derek Wright, her employer, attempted to require her to adhere to a dress code that included a “No Bra Thursday”. She alleged that he regularly discussed Anderson’s breast size with her in front of other employees.

Richard Branson, the owner of Virgin Rail in Britain, cause a row among his female train attendants when he introduced new uniforms in May 2013. A number of them complained that the new blouses they are required to wear are too revealing and expose their brassieres to the public. Virgin Rail offered a voucher worth ₤20 to allow the unhappy employees to purchase a top to wear underneath the new blouses.